What is the lifecycle of an Andean sparrow?

In 1958, Alden Miller, longtime director of the MVZ, took a sabbatical for the entire year in order to study Zonotrichia sparrows in Colombia, funded by a prestigious Guggenheim grant. At the time, very little was known about the nesting of equatorial birds, who unlike their Northern relatives of the same genus, enjoyed warm weather year round in which to raise their young. Alongside his Zonotrichia study, Miller continued to collect for the MVZ, bringing back vertebrate specimens ranging from a bear to hylid frogs for the collection and insects for the Berkeley Entomology department. A colleague of Miller’s from the MVZ wrote to him: “…I found all the curators excitedly unwrapping your specimens… What gaudy birds you find!” [A.S. Leopold Jun. 10, 1958] Spending much of his time at a research station near Santo Domingo for daily observations of the Zonotrichia lifecycle and nesting, Miller also wrote for the University of Bogota and gave bilingual presentations at the Universidad del Valle. With a colleague he went on expeditions to collect in the Putumayo jungle, the Central Andes, and other regions of the Amazon basin. Miller’s proposal that Zonotrichia capensis undergo a double annual molt was both questioned and complimented by MVZ colleagues who asked Miller to, “forgive my skepticism” [A.S. Leopold Sept. 29, 1958] and praised his observation as “absolutely fabulous” [F.A. Pitelka Oct. 30, 1958].

Who collected the tropical fauna of Colombia?

Miller traveled to Colombia accompanied by his wife Virginia and two daughters, Barbara and his “favorite secretary” Patricia. Of Virginia, a colleague of Miller’s wrote, “She was at his side in the field at every opportunity… There she helped him weigh specimens, skin birds and mammals, inject reptiles and amphibians, and flesh out skeletons” [R.A Stirton Jan. 19, 1966]. In Colombia he joined experienced ornithologist and collector Dr. F. Carlos Lehmann V, director of the Museo Departamental de Historia Natural del Valle who accompanied him on expeditions and provided Miller with specimens from regions they were unable to visit as a group. On one expedition, a local boy and his white mutt dog guided them, helping to find fallen birds. Deep in the Putumayo jungle, Lehmann came down with malaria and a fever of 104 and although Miller radioed for an army plane, “4 days later he wanted to drive his car out himself.” [A. H. Miller Nov. 24, 1958]

What tools and technologies were needed in the field?

"Our equipment, planned and assembled,” wrote Miller, “seems reasonably complete and adequate -operating lamps, ammunition, photometer, etc." [A.H. Miller March 20, 1958] The tools of collection on the expedition consisted of Bailey and net traps and guns. In addition to his trained eye, Miller used binoculars for closer observations of plumage, especially to determine if birds were molting. Between the aid of the MVZ and Carlos Lehmann, Miller was kept supplied with large quantities of museum labels, aluminum bird bands, and .38 shells, collecting birds in the rainforest canopy as high up as 50 feet. Miller used the work of a microtechnician to embed and section the several hundred tissue samples he planned to bring back. Although many of the Zonotrichia studied by Miller were banded, retrapped, and even underwent laparotomy surgeries in a nonlethal study, Miller also brought back 83 Zonotrichia specimens. Highly skilled at field surgeries, Miller used calipers to measure testis size, releasing the sparrows into the wild within an hour, sometimes with only scotch tape as a suture. The hardy sparrows would resume their singing and normal behavior as usual.

What did Miller write about?

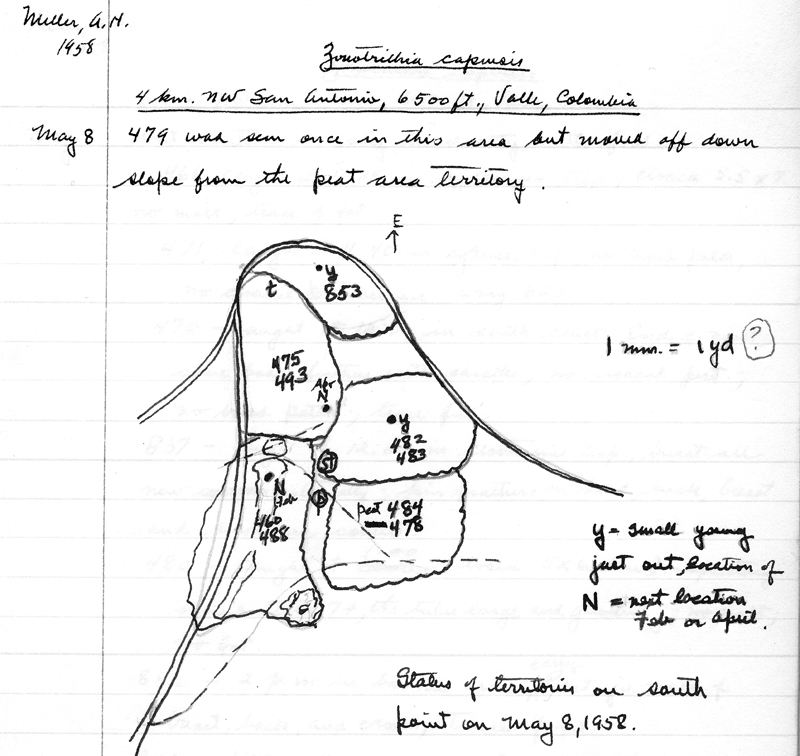

Miller wrote three volumes of field notes during his year in Colombia, cataloguing his work with Zonotrichia and the remarkable range of animals from porcupines to toucans to coral snakes encountered in his travels. His notes reflect an ear attentive to bird vocalizations. His Zonotrichia journal describes Miller waking up at the crack of dawn to check on nests near his house, the young nestlings “eyeing him alertly,” his observations on territoriality, and his work. Miller used net traps to catch and release banded birds, studying physical changes as they matured. He followed the lifecycles of Zonotrichia such as the pair nicknamed “Yellow” and “Red” as they nested and raised their offspring. His observations while collecting for the museum were equally detailed, filled with ideas on physiological adaptations for survival in the tropics, and comparisons between familiar northern birds and their exotic equatorial relatives. Extensive fieldwork was a time-honored tradition in the MVZ and Miller sought to produce field notes in the spirit of the original guidelines set down by the first MVZ director, Joseph Grinnell.