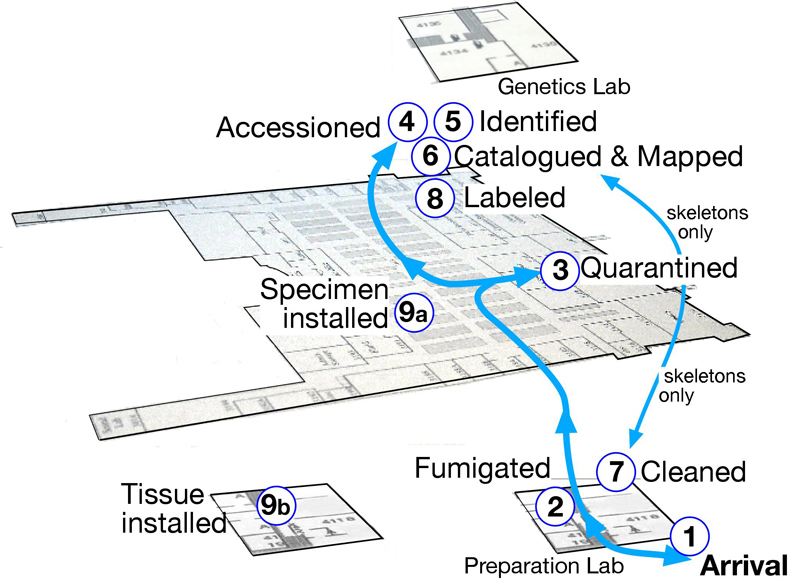

Path of a Bird

In the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology

The blue pathway shows how birds, like the Andean sparrow in the picture, have entered the research collection. Click on a number in the map below to learn what happens at each stage.

Alden Miller returned from Colombia after trips in 1958 and 1959 with more than 1200 bird specimens. Most of these were prepared as bird skins in the field, but 168 were made into skeletons to be cleaned in the Museum. Miller was studying the Andean Sparrow and brought back 83 specimens of them (73 skins and 10 skeletons).

Alden Miller returned from Colombia after trips in 1958 and 1959 with more than 1200 bird specimens. Most of these were prepared as bird skins in the field, but 168 were made into skeletons to be cleaned in the Museum. Miller was studying the Andean Sparrow and brought back 83 specimens of them (73 skins and 10 skeletons). Miller's specimens were fumigated with chemicals when they arrived in the Museum to kill any pests that might be living in the feathers or partly prepared skeleton and which could destroy the specimen. Today, specimens are deposited directly into a freezer for at least one week to control potential pests. Freezing became common practice in the MVZ in 2004.

Miller's specimens were fumigated with chemicals when they arrived in the Museum to kill any pests that might be living in the feathers or partly prepared skeleton and which could destroy the specimen. Today, specimens are deposited directly into a freezer for at least one week to control potential pests. Freezing became common practice in the MVZ in 2004. Skins and skeletons are removed from the freezer and quarantined for one week or more before being checked for live insects that may have survived freezing.

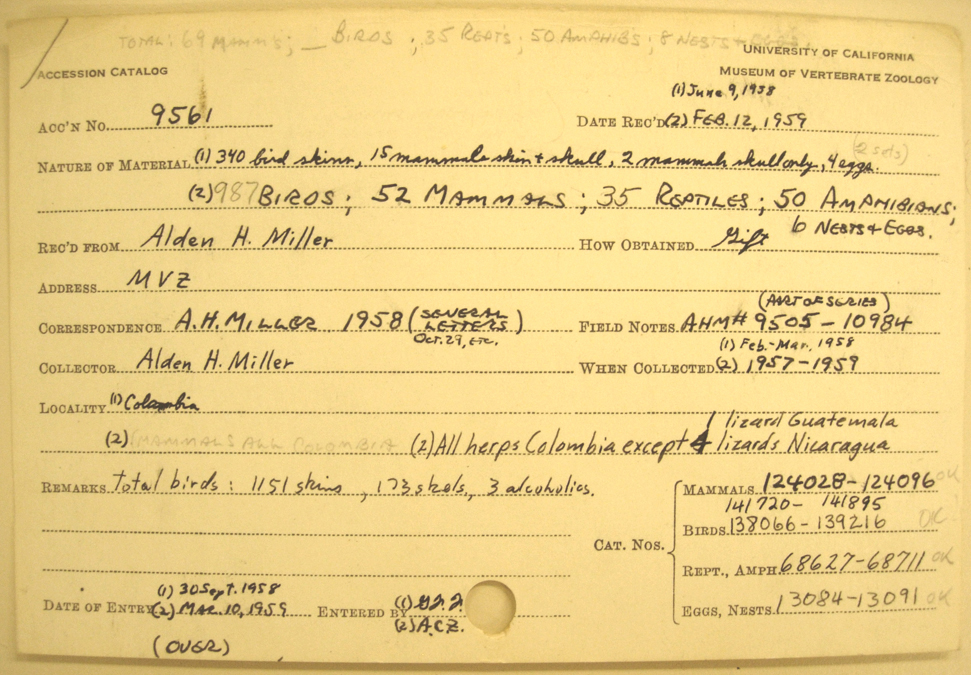

Skins and skeletons are removed from the freezer and quarantined for one week or more before being checked for live insects that may have survived freezing. Bird skins and skeletons are brought back with a field catalog and paper records of permits, and are assigned an accession number that includes all of the specimens from an expedition. When Miller was working in Colombia, he also collected bird nests and eggs, mammals, reptiles, amphibians. The entire set of specimens from Miller’s trips to Colombia have the accession number 9561. Today, bird researchers also routinely collect other kinds of material in addition to skins and skeletons, such as tissue and stomach samples, parasites, and audio recordings. All of these would be part of the same accession.

Bird skins and skeletons are brought back with a field catalog and paper records of permits, and are assigned an accession number that includes all of the specimens from an expedition. When Miller was working in Colombia, he also collected bird nests and eggs, mammals, reptiles, amphibians. The entire set of specimens from Miller’s trips to Colombia have the accession number 9561. Today, bird researchers also routinely collect other kinds of material in addition to skins and skeletons, such as tissue and stomach samples, parasites, and audio recordings. All of these would be part of the same accession. Using the field catalog, all of the specimens are inventoried and ordered taxonomically and geographically. The collector usually determines the specimen's genus and species in the field, while the curator or student assistant typically identifies specimens to subspecies based on the skin and/or the location. Although most bird species are easily recognized, identification of the more difficult groups (for example, Empidonax flycatchers) may require use of vocalizations, habitat, and DNA in addition to morphology and plumage.

Using the field catalog, all of the specimens are inventoried and ordered taxonomically and geographically. The collector usually determines the specimen's genus and species in the field, while the curator or student assistant typically identifies specimens to subspecies based on the skin and/or the location. Although most bird species are easily recognized, identification of the more difficult groups (for example, Empidonax flycatchers) may require use of vocalizations, habitat, and DNA in addition to morphology and plumage. Each specimen is assigned a unique MVZ bird catalog number, and all parts from one animal receive the same number. Information about Miller's Colombian specimens was entered onto paper catalog cards. Today, information is entered into a digital database. Most of the same kinds of information are recorded, but additional data include GPS coordinates and permit information. After the specimen information is entered into the database, it is checked and uploaded for online access. Geographic coordinates are added to the record if no GPS information is given by the collector. All localities and coordinates are then verified by a georeferencing team.

Each specimen is assigned a unique MVZ bird catalog number, and all parts from one animal receive the same number. Information about Miller's Colombian specimens was entered onto paper catalog cards. Today, information is entered into a digital database. Most of the same kinds of information are recorded, but additional data include GPS coordinates and permit information. After the specimen information is entered into the database, it is checked and uploaded for online access. Geographic coordinates are added to the record if no GPS information is given by the collector. All localities and coordinates are then verified by a georeferencing team. Skeletons are cleaned and stored separately from skins. Bones used to be cleaned by hand, which involved boiling them in water with chemical treatment. Since 1930, skeletons have been cleaned by dermestid beetles, a method which better preserves the tiny bones of birds. This method of cleaning was introduced by the MVZ preparator. After being cleaned by the beetles, skeletons are frozen again to prevent beetles from entering the collection.

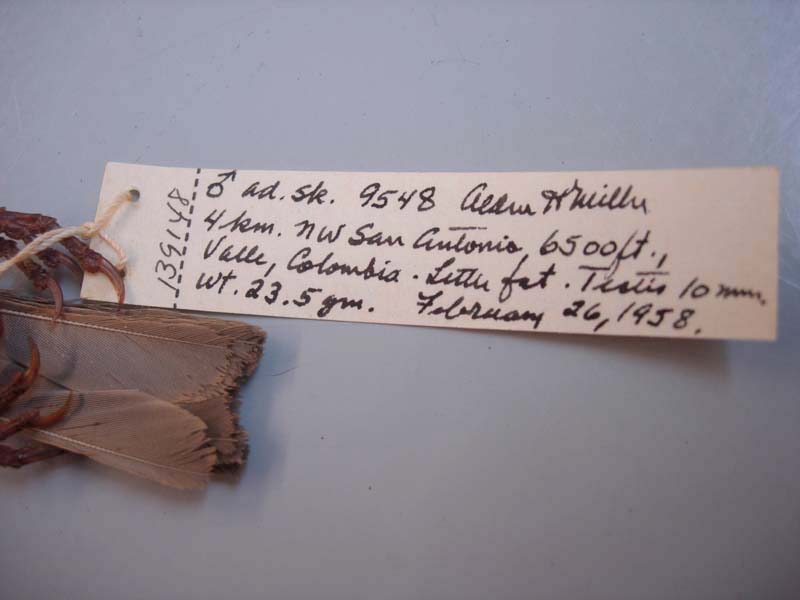

Skeletons are cleaned and stored separately from skins. Bones used to be cleaned by hand, which involved boiling them in water with chemical treatment. Since 1930, skeletons have been cleaned by dermestid beetles, a method which better preserves the tiny bones of birds. This method of cleaning was introduced by the MVZ preparator. After being cleaned by the beetles, skeletons are frozen again to prevent beetles from entering the collection. The collector ties a tag to the bird skin or skeleton in the field. Skin tags include the collectors name and field number, locality, date, age, sex, breeding condition, weight, fat, and sometimes bill or foot color. Skeleton tags are smaller and heavier, and include only the collector’s initials and field number, plus sometimes the sex and weight of the bird. The MVZ catalog number is added to both kinds of tags after the specimen is catalogued in the Museum, and the genus, species, and subspecies name is written in pencil to allow for taxonomic re-naming. If the specimen is a skeleton, it is placed in a box with labels generated from the database.

The collector ties a tag to the bird skin or skeleton in the field. Skin tags include the collectors name and field number, locality, date, age, sex, breeding condition, weight, fat, and sometimes bill or foot color. Skeleton tags are smaller and heavier, and include only the collector’s initials and field number, plus sometimes the sex and weight of the bird. The MVZ catalog number is added to both kinds of tags after the specimen is catalogued in the Museum, and the genus, species, and subspecies name is written in pencil to allow for taxonomic re-naming. If the specimen is a skeleton, it is placed in a box with labels generated from the database. Bird skins are arranged taxonomically by order, family, genus, species, and subspecies, and then ordered geographically by locality. If there is a series of birds from the same place, then they are ordered by month and day of collection. Bird skeletons, eggs, and nests are arranged taxonomically to the level of family, and then alphabetically by genus, species, subspecies, and location. Each type of collection is stored in a separate case.

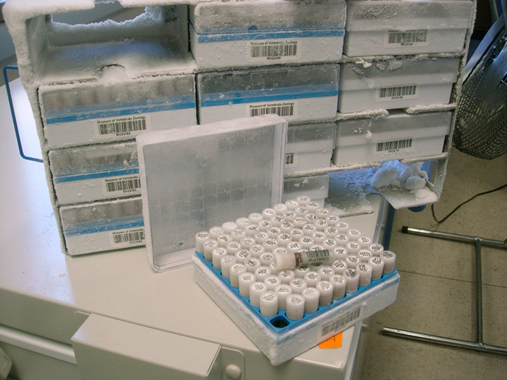

Bird skins are arranged taxonomically by order, family, genus, species, and subspecies, and then ordered geographically by locality. If there is a series of birds from the same place, then they are ordered by month and day of collection. Bird skeletons, eggs, and nests are arranged taxonomically to the level of family, and then alphabetically by genus, species, subspecies, and location. Each type of collection is stored in a separate case. Miller took tissue samples of Andean sparrows for protein analysis, but these were not kept as part of a tissue collection. Today, tissue samples are typically taken in the field in liquid nitrogen or buffer, and then stored at ultra-low temperatures to preserve proteins, DNA, and/or RNA for analysis. The frozen tissue collection started in the early 1970s, and freezing tissue became standard practice in the mid-1980s. Bird tissues were stored in ultra-low freezers, but were transferred in 2010 to liquid nitrogen storage for longer-term archival preservation.

Miller took tissue samples of Andean sparrows for protein analysis, but these were not kept as part of a tissue collection. Today, tissue samples are typically taken in the field in liquid nitrogen or buffer, and then stored at ultra-low temperatures to preserve proteins, DNA, and/or RNA for analysis. The frozen tissue collection started in the early 1970s, and freezing tissue became standard practice in the mid-1980s. Bird tissues were stored in ultra-low freezers, but were transferred in 2010 to liquid nitrogen storage for longer-term archival preservation.