Path of a Mammal

In the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology

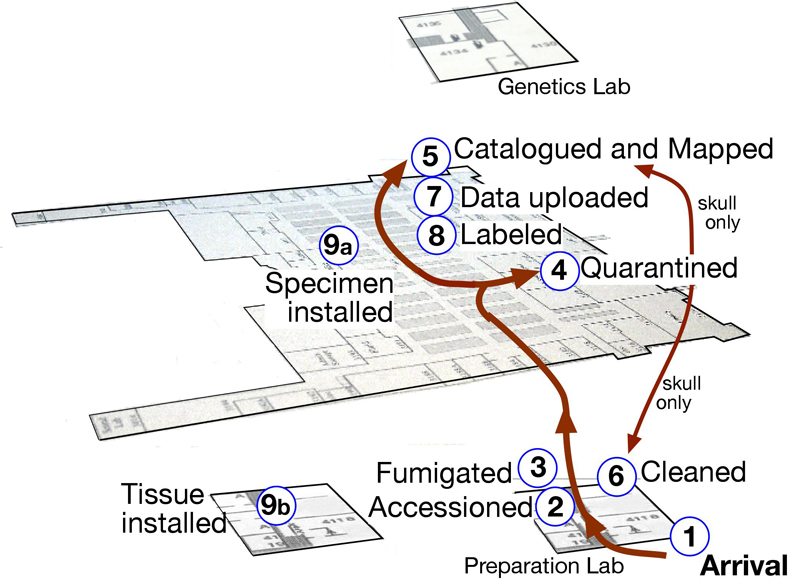

The red pathway shows how mammals, like the pocket gopher in the picture, have entered the research collection. Click on a number in the map below to learn what happens at each stage.

Collectors returned to the MVZ from fieldwork in the San Jacinto region with thousands of specimens. There are over 20,000 pocket gophers in the MVZ; they have been collected from the earliest days and have been an important focus of research up to the present. Mammal skins and skulls are usually prepared in the field. Both are diagnostic for species identification.

Collectors returned to the MVZ from fieldwork in the San Jacinto region with thousands of specimens. There are over 20,000 pocket gophers in the MVZ; they have been collected from the earliest days and have been an important focus of research up to the present. Mammal skins and skulls are usually prepared in the field. Both are diagnostic for species identification. The mammal and all of the specimens from its expedition are assigned one accession number from the Accession Catalog. Specimens from the 1908 San Jacinto expedition received the number 6. There are today more than 14,600 accessions. Accession cards are still used and show a summary of all the materials related to a collecting expedition, such type of specimen (mammals, reptiles, etc), field notes and correspondence, dates and localities of collection, permits, date and author of card entry, and information relating to how the material was received.

The mammal and all of the specimens from its expedition are assigned one accession number from the Accession Catalog. Specimens from the 1908 San Jacinto expedition received the number 6. There are today more than 14,600 accessions. Accession cards are still used and show a summary of all the materials related to a collecting expedition, such type of specimen (mammals, reptiles, etc), field notes and correspondence, dates and localities of collection, permits, date and author of card entry, and information relating to how the material was received. The 1908 San Jacinto expedition used chemicals to fumigate specimens to kill any insects or pests that might be living in the fur or bones. Today, mammal skins and skeletons are deposited directly after arrival into a freezer for at least one week to control potential pests. Freezing became common in 2004.

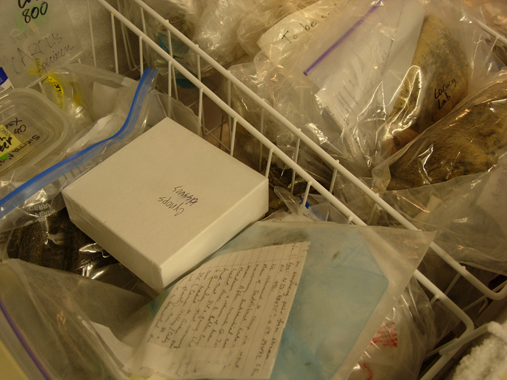

The 1908 San Jacinto expedition used chemicals to fumigate specimens to kill any insects or pests that might be living in the fur or bones. Today, mammal skins and skeletons are deposited directly after arrival into a freezer for at least one week to control potential pests. Freezing became common in 2004.  The skins and skulls are kept in containers in a closed, secure room for a week or more and checked for evidence of any live insects that may have survived freezing.

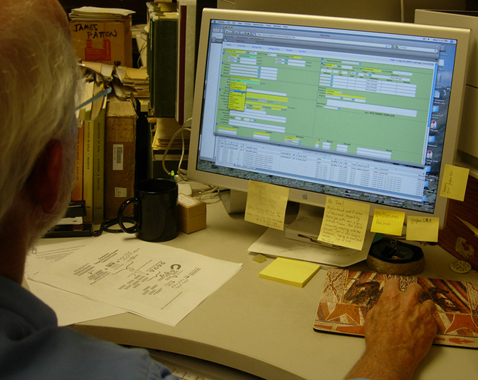

The skins and skulls are kept in containers in a closed, secure room for a week or more and checked for evidence of any live insects that may have survived freezing. With all the specimens and field catalog gathered, the specimens are taxonomically ordered and a unique number is assigned to each specimen in a spreadsheet. All parts from one animal receive the same catalog number. In 1908, information about the San Jacinto expedition specimens was entered onto catalog cards. Today, information is entered into a digital database. Many of the same information points are recorded, but today much more information is entered, including GPS coordinates and permit information. After data entry, records are printed onto a paper ledger. Geographic coordinates are added to the record if there is no GPS information given by the collector. All coordinates are then verified by a geo-referencing team, which makes sure that the location is correct and adds a maximum uncertainty radius.

With all the specimens and field catalog gathered, the specimens are taxonomically ordered and a unique number is assigned to each specimen in a spreadsheet. All parts from one animal receive the same catalog number. In 1908, information about the San Jacinto expedition specimens was entered onto catalog cards. Today, information is entered into a digital database. Many of the same information points are recorded, but today much more information is entered, including GPS coordinates and permit information. After data entry, records are printed onto a paper ledger. Geographic coordinates are added to the record if there is no GPS information given by the collector. All coordinates are then verified by a geo-referencing team, which makes sure that the location is correct and adds a maximum uncertainty radius. After receiving a catalog number, skins are held in drawers and tissues are installed in a freezer (See 9a). Skulls are sent to the Preparation Lab to be cleaned. Skulls from the 1908 San Jacinto expedition were cleaned by hand, which involved the Curator in Osteology boiling them in water with chemical treatment. Today, after the catalog number is written on the skull tag that was attached in the field, skulls are cleaned by dermestid beetles. This method of cleaning was introduced to the MVZ in 1930 by its Preparator. After being cleaned by the beetles, the skulls are frozen again to prevent beetles from entering the collection.

After receiving a catalog number, skins are held in drawers and tissues are installed in a freezer (See 9a). Skulls are sent to the Preparation Lab to be cleaned. Skulls from the 1908 San Jacinto expedition were cleaned by hand, which involved the Curator in Osteology boiling them in water with chemical treatment. Today, after the catalog number is written on the skull tag that was attached in the field, skulls are cleaned by dermestid beetles. This method of cleaning was introduced to the MVZ in 1930 by its Preparator. After being cleaned by the beetles, the skulls are frozen again to prevent beetles from entering the collection. The collector usually determines the specimen's genus and species, and most are known. If the species is questionable, the specimen is compared to others in the collection or in publications. Occasionally a specimen waits for special studies in order to be identified to species. Mammal skulls are often diagnostic, so when the skull returns from cleaning a final determination can be made for questionable specimens. Then the spreadsheet is completed, checked with specimens and all data uploaded to the online specimen database.

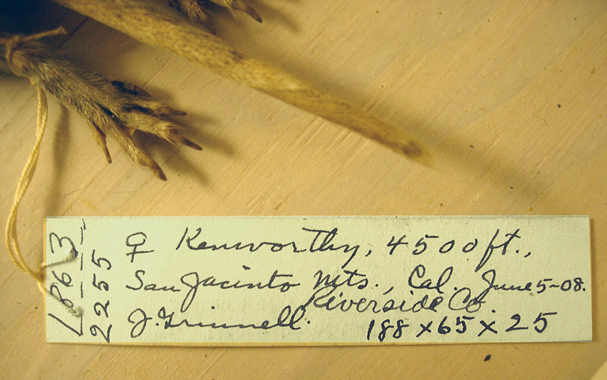

The collector usually determines the specimen's genus and species, and most are known. If the species is questionable, the specimen is compared to others in the collection or in publications. Occasionally a specimen waits for special studies in order to be identified to species. Mammal skulls are often diagnostic, so when the skull returns from cleaning a final determination can be made for questionable specimens. Then the spreadsheet is completed, checked with specimens and all data uploaded to the online specimen database. A tag is tied to the specimen with the collector's field number, sex, measurements, locality, date, and collector's name. After cataloguing, the MVZ number is added to this tag. The genus and species name is written in pencil to allow for taxonomic re-naming. The skull and jaw each have the catalog number written on the bone and are placed in a labeled box or glass vial.

A tag is tied to the specimen with the collector's field number, sex, measurements, locality, date, and collector's name. After cataloguing, the MVZ number is added to this tag. The genus and species name is written in pencil to allow for taxonomic re-naming. The skull and jaw each have the catalog number written on the bone and are placed in a labeled box or glass vial. The skin and its skull are arranged alphabetically, by family, genus, species, and subspecies, then by geographical area, on a tray in a large gray metal case for long term storage. Whole-skeleton mammal specimens are stored separately.

The skin and its skull are arranged alphabetically, by family, genus, species, and subspecies, then by geographical area, on a tray in a large gray metal case for long term storage. Whole-skeleton mammal specimens are stored separately. Today, tissue samples are taken in the field and stored in ethanol, one of several different buffers, or frozen in liquid nitrogen to preserve proteins and DNA for analysis. The frozen tissue collection started in the early 1970s, but freezing tissue only became standard practice in 1994. Although tissue samples were not taken during the San Jacinto expedition, these skins are potentially available today to sample for genetic analysis.

Today, tissue samples are taken in the field and stored in ethanol, one of several different buffers, or frozen in liquid nitrogen to preserve proteins and DNA for analysis. The frozen tissue collection started in the early 1970s, but freezing tissue only became standard practice in 1994. Although tissue samples were not taken during the San Jacinto expedition, these skins are potentially available today to sample for genetic analysis.